The first to make headlines was Columbia: “Trump administration cancels $400 million in federal dollars for Columbia University.” Then they doubled down at Hopkins: “Johns Hopkins to lose 2,000 jobs after Trump’s $800m cut in USAid funding.” The assault was not merely financial but terroristic, as demonstrated by the fear induced by the arrest of Mahmoud Khalil back at Columbia. Then they combined the approaches: “Trump administration suspends $175 million in federal funding for Penn over transgender swimmer.”

Faculty, staff, and students immediately reacted, especially on social media, by decrying the cuts and their impact, not only on themselves but on everyone who stands to benefit from their research aimed at addressing the critical challenges of our day. It became the impetus for many to participate in the Stand Up for Science protests held around the country on March 7th. The assaults were soon being described as a “War on Universities” and an “authoritarian takeover” (paywalled) of higher education. Yet to the bafflement and frustration of faculty and students, and in spite of the fact that 94% of the university presidents surveyed at the Yale Higher Education Leadership Summit agreed that “the Trump Administration is at war with higher education,” individual university presidents have largely been reticent to say much in the way of anything publicly at all.

That changed yesterday when Christopher L. Eisgruber, president of Princeton, came out swinging in The Atlantic (paywalled): “The attack on Columbia is a radical threat to scholarly excellence and to America’s leadership in research. Universities and their leaders should speak up and litigate forcefully to protect their rights.”

Why is it left to the president of Princeton to take the lead here? Princeton has not really been a character in the story to this point, and does not seem to have been targeted in the way some of its Ivy League peers have. Why should it draw attention to itself now? Is Eisgruber just particularly courageous, or particularly eloquent, and so makes a good figurehead among his peers? Personally, I do find that he is generally both more courageous and more eloquent than many other university presidents, but then again, he can afford to be.

Princeton’s financial overview indicates that 15% of its revenue “comes from federal and non-federal grants and contracts. This includes federally funded student aid.” Brown, by contrast, while like Princeton lacking patient care infome, reports that 22.1% of their income comes from sponsored research, not all of which is federal, but much likely is, and this does not include student aid. Dartmouth reports 14.3% of revenue is sponsored research, again with no medical income and not including student aid.

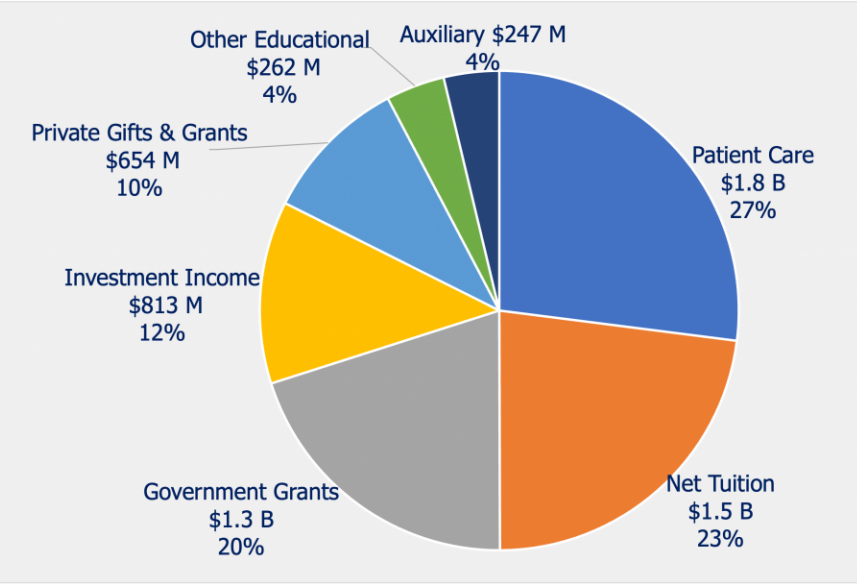

Columbia provides a pie chart of it’s revenue, indicating that 20% of its revenue, not including student aid, comes from government grants and contracts:

Harvard reports that “Research: Federal and Non-Federal sponsored revenue” is 16% of its annual revenue, while Yale shows:

Things are somewhat murkier in the financial report from UPenn because the 7.8% of revenue derived from sponsored programs is counterbalanced by the fact that 60% of their revenue is from patient services at their hospitals, so more useful is The Daily Pennsylvanian‘s figure: “Penn received over $1 billion in federal funding in 2024, DP analysis finds.” An interesting contrast is Cornell, which financial guide indicates that 17% of revenue comes from sponsored programs, counterbalanced by only 31% of revenue from medical services, which more closely mirror’s Yale’s 29%. Running your own hospital system makes your finances look a lot different.

Decamping from the Ivy League, Johns Hopkins is quite interesting because they report that over 54% of their operating revenue comes from sponsored research. While Hopkins is knows as the “No. 1 recipient of federal research funds,” it should be noted that over half of that 54% comes from contract revenues from their Applied Physics Laboratory. Their income from clinical services, by contrast, generates only 11% of their revenue.

Another outspoken president is Wesleyan University’s Michael Roth, who was recently quoted in Politico being quite critical of his peers who rely on the principle of “institutional neutrality” as grounds for staying out of the fray: “The infatuation with institutional neutrality,” he said, “is just making cowardice into a policy.” Wesleyan reports that just over 3% of their revenue comes from government and foundation grants.

I always find it interesting and elightening to consider institutional metrics against those of the institutions where I have been affiliated. Brandeis University reports sponsored programs making up 19.6% of its revenue, whereas at my alma mater, Ithaca College reports just shy of 3%. Boston University provides a nice five-year trend graph in its report, showing sponsored program revenue generally holding steady at 22% of overall revenue:

What can we make of all of this? Well, it does appear that the more of their budget a university president has at stake, the less likely they are to speak up publicly and directly in the face of what is quickly become an unrelenting assault on colleges and universities. Princeton and Wesleyan are just far less reliant on government funds than many other of the most prominent institutions, and so are more able to stand up to this sort of bullying. Eisgruber identified this dynamic at play in his piece in The Atlantic: “If the United States government ever repudiated the principle of academic freedom, it could bully universities by threatening to withdraw funding unless they changed their curricula, research programs, and personnel decisions. That’s what the Trump administration did this month.”

As I often remind people who find themselves bewildered by the dynamics and decisions made by universities and their leaders, it is important to remember that in spite of all of the legitimate concerns about the commodification, commericialization, and corporatization of higher education, universities fundamentally remain medieval institutons characterized by vassalage and patronage. The more the federal government is your patron, the more you are their vassal and they your liege lord, and the more likely your leaders are to bend the knee.

I would love to be proven wrong, and I know that many of my friends and collegues at colleges and universities across the country would prefer their presidents take a stronger stand. Given the potential for lasting, irreversable damage not only to the institutions and the people that work in them, but to all of the good that comes out of that work, it is certainly reasonable to question the virtue of a proportional response.

But, just as President Bartlett settled for the proportional response in the end, I suspect most university leaders will as well, and that while this will involve some strong language and some degree of resistance, it will also involve a fair bit of caving to the demands being made of them, especially since a number of them seem to agree with the criticisms underlying those demands.

Given the gravity of the assault, it seems to me that most leaders have yet to rise to what might be considered an adequate level of proportionality, Eisgruber and Roth excepted. At the same time, I can sympathize with university leaders who feel stuck between a rock and a hard place: it is unclear their institutions can survive either caving to the demands of the federal government or to forgoing the federal funds on which they have come to rely. I have heard several university presidents echo the line that “nonprofit is a tax status, not a business model,” but the risks associated with building your business model on more and more funding for the federal government are being realized all at once, and they are far worse than many seemed to realize. What models universities may adopt to make themselves viable into the future remain to be imagined, let alone seen.

Leave a comment