Ryan Burge’s recent article in Asterisk Mag, “The Demons of Non-Denoms,” reminded me of his Graphs About Religion post from May, “How Many Megachurches Are There? Where Are They Located?,” and specifically the excellent map of megachurches linked therein, which is in turn based on the Hartford Institute for Religion Research Megachurch Database. As a Bostoninan, one of the first things I checked was how many megachurches there are here in New England.

Ten. There are ten megachurches in New England. Out of 1,578 nation-wide.

Notably, two of the ten are in New Hampshire. The other eight are in Massachusetts. The other four New England states–Connecticut, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Maine–are completely devoid of megachurches. According to Ryan’s map, the only other states with no megahurches are Delaware and Alaska. That means that two-thirds of all states without megachurches are in New England.

Honestly, this is not terribly surprising. New England is a region that prides itself on being made up of many relatively small cities and towns. Churches here tend to reflect the scale of the communities they inhabit, and so are likewise relatively small. (Megachurch = average weekly attendance > 2,000). It also does not help that the northeast generally is at the forefront of the secularizing trend in the U.S.

The good news about there only being ten megachurches in New England is that it is not terribly difficult to look them all up. So, I did.

Downtown Boston

Park Street Church was founded in 1809 as a trinitarian response to the unitarian wave spreading across the greater Boston area. “Our mission is to make disciples who become like Jesus, together.” Park Street hosts three services on Sundays at their church on “Brimstone Corner,” a landmark on the Freedom Trail, adjacent to the Boston Common. An important touchstone in the development of American evangelicalism, the church has a staff of twenty-four, apparently mostly white though with some racial diversity, and all staff with the title of minister appear to be male. The senior pastor always has been and remains a white male. The elders and officers are likewise predominantly white and male, with less than a quarter apparently non-white and less than a third appear to be women. While Park Street has historically prized advanced theological degrees among its clergy, its present senior pastor does not have a doctoral degree but does have a masters; he has been the focus of bitter division in the church.

Church of the Larger Fellowship (CLF) traces its history back to the missionary enterprises of the unitarians and universalists in the 1800s, and so represents the other side of the trinitarian/unitarian divide. “As a Unitarian Universalist congregation with no geographical boundary, the CLF creates global spiritual community, rooted in profound love, which cultivates wonder, imagination, and the courage to act.” The church does not gather in person but rather virtually, via Zoom, on Sundays and Mondays, hosts a robust multi-media platform that resources the Unitarian Universalist denomination, and sponsors notable ministries for military personnel and prisoners. On a staff of nine, only two are apparently male; five appear to be white. Of the nine affiliated ministers, who “ground their UU ministry in the liberatory practice of CLF, and represent our congregation in the wider denomination and in the world,” four are apparently male and all appear to be white. CLF’s nine-member board of directors is likewise predominantly female, with only one apparently male, and eight of the nine appear to be white. Both members of the lead ministry team hold terminal degrees, albeit not in theology: one holds a master of divinity degree and a PhD in cell biology, while the other holds a master of social work.

Mattapan

Morning Star Baptist Church is a full gospel Black Baptist congregation founded in 1965. “Morning Star Bapist Church is committed to improving the quality of spiritual and economic life for its membership and for residents of the surrounding community.” The church has inhabited its location on Blue Hill Avenue in Mattapan since 1976, where it gathers at 10am on Sundays, and online. A staff of twelve, led by their male bishop, otherwise appears to be predominantly (75%) female. Unsurprising for a Black church, the staff appears to be predominantly, if not exclusively, African American. Some of the clergy, including the bishop, have undertaken theological education from institutions ranging from Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary to Harvard Divinity School, and several have degrees in counseling.

“A church without walls,” Jubilee Christian Church is another Black church on Blue Hill Avenue in Mattapan, now with satellite locations in Stoughton and Worcester, and online. “We are a House of Prayer called to Encounter God, Empower Believers, Equip Disciples and Expand in Community.” The church professes beliefs that mark it as broadly evangelical, but also articulate scripture based “culture keys” that are quite distinctive, such as “Health 360: We strive to be spiritually, physically, financially, and emotionally healthy” and “Legacy Builders: We live every day with the past, present and future generations in mind.” The only staff listed are the two senior pastors, the son of the founding pastor and his wife, neither of whom have undertaken theological education.

Inside 128

The Boston Church of Christ begain 1979 when Kip McKean moved to Lexington, Massachusetts to pastor in the Lexington Church of Christ, which soon changed its name to the Boston Church of Christ, eventually splitting from the Churches of Christ to become the International Church of Christ. McKean departed in 2003 amidst controversey, going on to found the International Christian Church, but the church remains controversial due to coercive recruiting practices and accusations of spiritual and sexual abuse. Now meeting in seven towns in greater Boston, with a gathering in Spanish in Arlington, their mission statement is the relatively anodyne “We are committed to bringing authentic Christianity to Eastern Massachusetts.” Their website provides no information about the leadership of the church or its governance.

Grace Chapel of Lexington, Massachusetts identifies as non-denominational and multicultural with four campuses in the suburbs of Boston and an online ministry. “We strive to be a vibrant, growing, multicultural community of seekers and believers, discovering life with God for the good of the world.” They boast a massive staff of sixty, well over half of whom appear to be female, and about a quarter appear to be of color. Of the thirteen staff with the title of pastor, seven appear to be female, and four appear to be of color. Of the six with theological eduation, most are from evangelical institutions, especially Gordon Conwell Theological Seminary, but one is from a Roman Catholic seminary; the pastor for care and support has a clinical psychology doctorate from Harvard. Grace Chapel is currently searching for a new senior pastor.

Outer Greater Boston

Calvary Chapel of Boston is not, in fact, in Boston, but rather in Rockland, Massachusetts on the South Shore. It is not clear that the Calvary Church of Boston would qualify as a megachurch on its own based on its weekly attendance, (it claims 1,000 weekly). It appears that the database on which Ryan’s map was built combined it with other members of the Calvary Chapel Association (CCA) in the greater Boston area, perhaps because their pastor, Randy Cahill, exercises oversight of at least some of them. The Boston church in Rockland says, “We believe that the only true basis of Christian fellowship is His (Agape) love, which is greater than any differences we possess and without which we have no right to claim ourselves Christians.” The CCA traces its founding to 1965 when Chuck Smith began a ministry in Costa Mesa, California, and now claims over 1,800 fellowships globally. Cahill appears to be a white male, as do the pastors of all of the other CCA churches in the greater Boston area for whom any information is readily available. Only one lists any theological education, both a master of divinity and a doctor of ministry from Alliance Theological Seminary.

Liberty Churches in Shrewsbury, Massachusetts, affiliated with the Assemblies of God, is also questionable as a megachurch as they claim “more than 1,000 people in attendance during our two weekend services.” “Liberty Church exists to lead people to Jesus Christ and to make disciples, by reflecting His love, teaching His Word and demonstrating His power.” Liberty churches has a pastoral team of five, all of whom appear to be white and three of whom appear to be male, including the lead pastor. Two, neither of whom are the lead pastor, have bachelors degrees in theology, but no other theological training is indicated for any of the pastors. They have a further staff of eight, half of whom appear to be female, and six are apparently white. Their six member board of directors appears to be half female and five of the six appear to be of color.

New Hampshire

“Bethany Church is a gospel-centered community committed to helping people connect in meaningful ways so that we can grow closer to Jesus, support those in need and impact the world around us.” The church does not say much about its history, but it has two worship services on Sundays at its central location in Greenland, NH and one service each at its satellites in Raymond, NH and Kittery Point, ME. Their statement of faith and bylaws would seem to mark them as broadly evangelical. Bethany boasts a staff of nineteen, thirteen of whom appear to be women, though the four people with the title of “pastor” as well as the student ministry director and creative director all appear male. Five of the eight church elders, the governing board of the church, appear to be male. All of the elders and staff appear to be white. Unlike many non-denominational churches, all of the pastors at Bethany Church have graduate theological degrees according to their LinkedIn profiles.

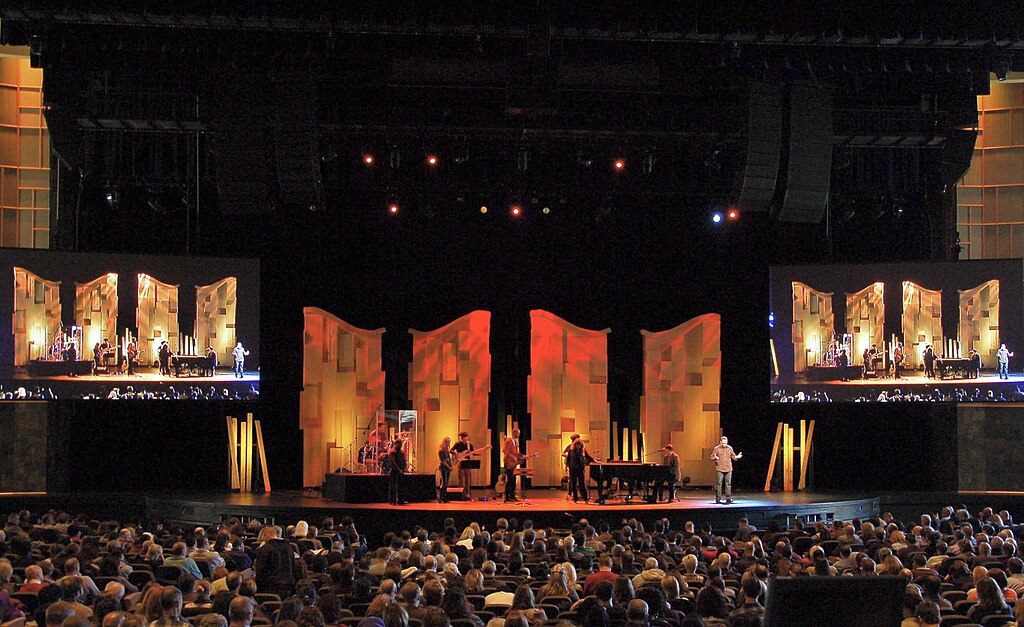

In 2022, Manchester Christian Church changed its name to One Church. “Our mission is to reach the most people in the shortest time by praying for One.” The church is spread across five sites in New Hampshire, one of which is just poised to open, plus an online community, each with multiple worship services each week. One Church spells out both its core beliefs and is core practices in concise terms, each with scripture references, all of which fit the broadly evangelical mold. The staff includes women with the title of pastor or associate pastor, and exhibits a modicum of racial diversity, though the senior pastor and all of the outpost pastors appear to be white men. The staff also includes one dog. All of the governing elders appear to be male. Some of the staff have attended bible or other Christian colleges, but the senior pastor has a degree in history and speech communication and the residency program the church sponsors focuses on “hands on experience” rather than theological education.

The New England Megachurch Vibe

What is odd about the ten megachurches in New England is not anything about any of the churches in particular but rather that there are megachurches in New England at all. As the Hartford Institute for Religion Research notes, over 70% of megachurches are in the south, in the suburban sprawl of large cities, with the largest concentrations in California, Texas, Florida, and Georgia. As megachurches go, the ones in New England are generally on the smaller side as all but one have an average weekly attendance below the national average of 4,092.

Generally, the Protestant identifications of the ten New England megachurches do follow the norm as all but two identify in ways that match 80% of megachurches nationally: nondenominational, Assemblies of God, Baptist, Christian, and Calvary Chapel. Those two are real outliers though: the Boston Church of Christ and the Church of the Larger Fellowship are the only megachurches in their respective affiliations in the whole country, the International Church of Christ and the Unitarian Universalist Association, respectively.

Seven of the ten churches also match the characteristic of having “a charismatic, authoritative senior minister.” Jubilee Christian Church has a charismatic, authoritative pair of senior ministers. The Church of the Larger Fellowship has a pair of lead pastors but their leadership seems, if anything, to deepmphasize charisma and authority. The leadership of the Boston Church of Christ is opaque, but historically it has had singular, charismatic, authoritative leadership.

There is one other way in which the Church of the Larger Fellowship stands out on this list. By definition, megachurches are Protestant. Are Unitarian Universalists Protestant? Historically speaking, they certainly emerged out of Protestant Christianity, but theologians and sociologists of religion are wont to tie themselves in knots trying to decide if they still qualify, much as they do regarding the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints.

So What?

Beyond being an exercise worthy of a masters level sociology of religion course, one could be forgiven for wondering why anyone would bother writing a post about megachurches in New England. I would suggest three reasons that anyone should be interested in what is going on with megachurches in their vicinity.

First, megachurches have outsized influence on other churches in their area. Commenting on the role of megachurches during the Covid-19 pandemic, researchers at the Hartford Institute for Religion Research note that “larger churches are providing much of the thought leadership for how to spiritually navigate the crisis—similar to how larger churches have been significant influencers in the years before the pandemic… In virtually every city and region, across denominations and less formal church networks, megachurch leaders continue to set the pace for other church leaders, both directly and indirectly.” Part of the reason for this is that megachurches interpret their size as indicative of divine favor, a contemporary instantiation of Max Weber’s famous Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. Other Christian leaders in the vicinity of these churches often accept this logic, either implicitly or explicitly, and so end up looking to the favored ones as models of how to themselves become favored.

Second, and In part because of the first point, megachurches end up setting the tone for what counts as Christianity around them. For Christians, being aware of this social dynamic can be important for regulating how they identify and work toward their own spiritual aspirations. For Christian leaders, it can be important for identifying divergences between the social norm and their own norms, and those of their congregation and denomination or affiliation. For non-Christians, it can be important for navigating relationships with Christians and checking assumptions. Of course, for four of the six New England states, that megachurch magnetism is notable primarily for its absence.

The final reason to pay attention to megachurches has to do with the fact that their influence, as described in the first two points, is inversely proportional to their accountability. The latest Hartford Institute for Religion Research report on megachurches notes that “the role of megachurch pastors cannot be emphasized enough.” Furthermore, its authors are correct that megachurch pastors are no more prone to scandal than their non-megachurch counterparts. “By and large, megachurch pastors are long-time servants of their churches. They keep the church’s focus on spiritual vitality, having a clear purpose, and living out that mission. And they eventually finish well.” Yet they perhaps underemphasize the extent to which the extraordinary growth megachurch leaders achieve, or at least strive for, is generated in most cases by a cult of personality surrounding the persona, leadership, and spiritual wisdom of the senior pastor. Such cults of personality diminish accountabilty by making it difficult to even question, let alone effectively constrain, the persona arond whom the cult has developed, as Ryan Burge describes in “The Demons of Non-Denoms.” To be sure, cults of personality can and do emerge in smaller churches as well, but they lack the influence megachurches have. The combination of high influence and low accountability leads to an extraordinary concentration of power, which is surely something everyone has a vested interest in keeping an eye on.

This post about New England megachurches is at least as odd as the fact that there are megachurches in New England, mainly because I am the one writing it. Megachurches are not at all central to my scholarly interests, and I am personally spiritually allergic to them, which is why I am part of a vanishingly small, dispersed, ecumenical religious order. That said, as a university chaplain I have provided spiritual care for students who attended several of these churches, which is how I first became atuned to their gravitational pull. Theologically, I am profoundly skeptical of the claim, whether made explicitly or implicitly, that the size of a church or the extent of its reach is any kind of meaningful sign of divine favor. Yet, I am very much aware of the fact that this is the norm against which I and the community I belong to are measured by many, and perhaps even most, outsiders, and I suspect we sometimes find ourselves wondering whether it might be true after all. To avoid that temptation, we would do well to attend to it.

Leave a comment