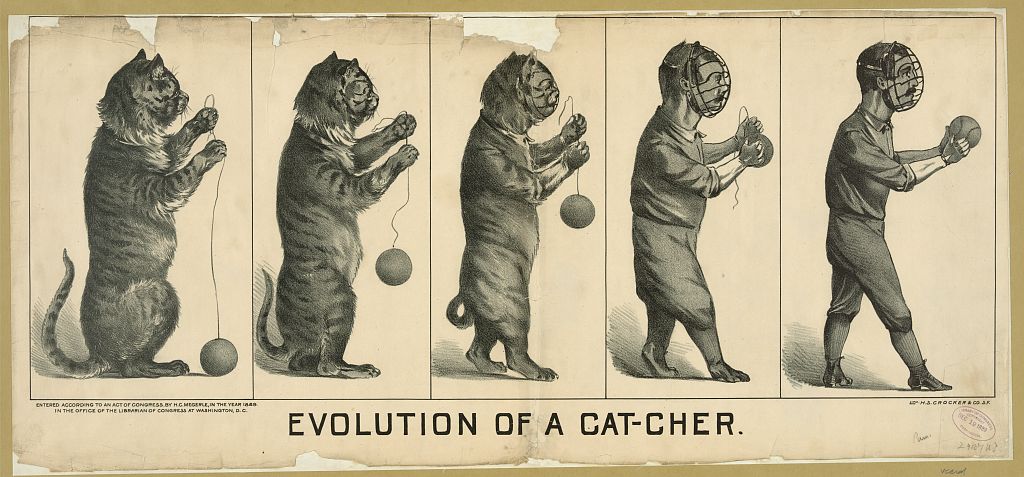

Anthropomoprhism is a fancy word for a very straightforward idea: the tendency to treat things that are not human as if they were. It is also a very old idea: the ancient Greek poet Xenophanes of Colophon was highly critical of the popular religion of his day for its tendency to ascribe human attributes to the gods. Anthropomorphism may be so intuitive and straightforward because our propensity to anthropomorphize is utterly pervasive: from pets to rocks to abstract shapes moving across a computer screen.

The Cognitive Science of Anthropomorphism

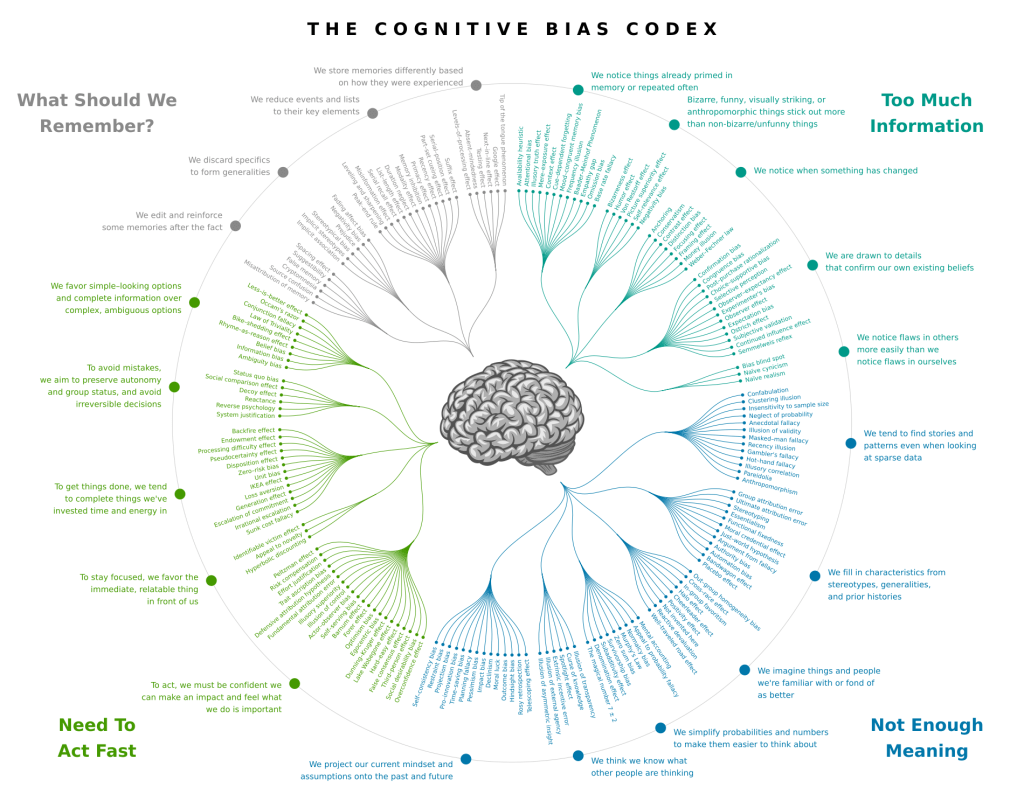

Cognitive Scientists recognize anthropomorphism as one of hundreds of cognitive biases. The term “bias” here is not pejorative but rather signals that judgment is arrived at by a process other than rationality. Many are highly adaptive. Rational thinking is more reliable but slow, whereas the heuristics, habits, conventions, and patterns that make up cognitive biases can be deployed almost instantaneously. If you suddenly perceive a lion approaching, you are more likely to survive if you follow your instinct to run than if you stand around waiting to confirm that there is in fact a lion. Anthropomorphism is a cognitive bias that stems from an insuffiency of meaning in the perceptual field. It is an attempt to fit a narrative or pattern to sparse data. It is reflexive because the narrative or pattern is us ourselves, in a sense extending our theory of mind beyond other humans to virtually anything at all. Why is the storm cloud thundering? Well, it must be angry since I make that kind of sound when I am angry.

Generally speaking, anthropomorphizing things is considered relativly benign, and can sometimes be rather amusing. Why won’t you replace your old clunker of a car? How dare you suggest my friends are replaceable! At the extreme, though, such anthropomorphically enhanced object attachment can lead to hoarding behavior. Companies frequently rely on the positive feelings induced in consumers by anthropomorphism, either in their marketing campaigns or in the design of the products themselves. Scientists tend to be leery of anthropomorphism, which is appropriate given the whole point of science is rational inquiry, but it turns out that anthropomorphism may actually be helpful in teaching science when its features and concepts are not yet clear. And while anthropomorphizing things may not be bad for you in most cases, it may not be so good for your pets.

When anthropomorphism becomes truly problematic, however, is as it approaches, and even extends beyond, its limit. That is, as the things being anthropomorphized actually do exhibit more and more characteristics in common with humans, the relatively harmless cognitive bias can turn into deeply disruptive cognitive dissonance. This is what we are seeing in some cases as regards chatbot interfaces with large language models (LLMs).

Anthropomorphizing AI

On June 11, 2022, The Economist published an article titled “Artificial neural networks are making strides towards consciousness, according to Blaise Agüera y Arcas.” Two days later, an editor’s note was appended to the article: “Since this article, by a Google vice-president, was published an engineer at the company, Blake Lemoine, has reportedly been placed on leave after claiming in an interview with the Washington Post that LaMDA, Google’s chatbot, had become ‘sentient.’” In explaining their subsequent firing of Lemoine in July, Google cited violations of company policies but also that his public claims regarding sentience were “wholly unfounded.” Come November 30, OpenAI released ChatGPT, a chatbot interface to its GPT-3.5 large language model. That put pressure on Google to release Bard (now Gemini), a chatbot interface to LaMDA, in February 2023, but its hallucination during rollout led Alphabet, parent company of Google, to loose $100 billion in market value. Having been told that the models underlying these chatbots were approaching consciousness but that claiming sentience was “wholly unfounded,” the general public was left to make sense of what this technology might be and be capable of.

Thankfully, a minority of the general public seems to be interpreting AI chatbots anthropomorphically, but those rates are growing quickly: 34% over twelve months. And while some instances of AI anthropomorphism are merely bizzare, such as the people who fall in love with chatbots, even to the point of marrying them, others are profoundly disturbing. “In the final moments before he took his own life, 14-year-old Sewell Setzer III took out his phone and messaged the chatbot that had become his closest friend,” begins one news story. Some have become obsessed with their AI chatbots to the point of suffering from AI psychosis. And children are struggling to distinguish AI agents they engage with from real humans in ways that are likely to be developmentally disruptive. Moreover, AI developers are well aware of the human propensity toward anthropomorphism and intentionally design their systems toward it, both in general and specifically to stand in for romantic partners or therapists. (Have you seen other examples of AI anthropomorphism? Submit them for inclusion in the Archive of Anthropomorphized AI).

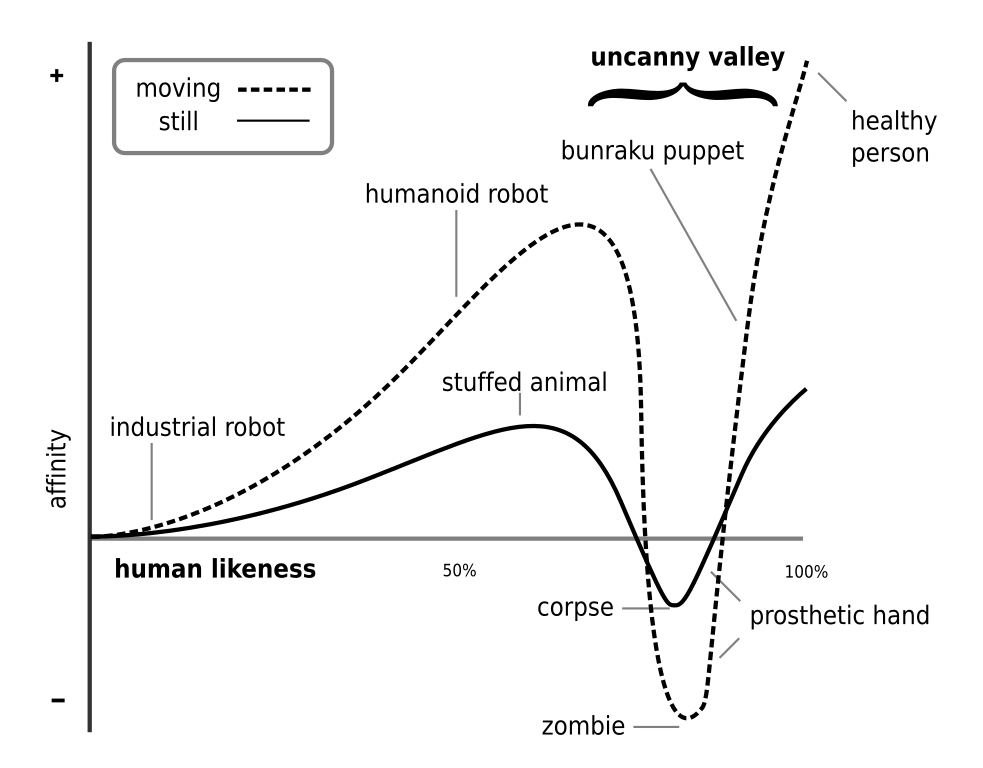

Artificial intelligence researchers have long recognized the potential for machines to approximate certain human characteristics and capacities and for humans to feel ambivalent about such developments. In 1949, Alan Turing developed his famous imitation game, in which an independent evaluator attempts to discern which participant in a conversation is human and which a machine based on a transcript of their natural-language conversation, as a measure of the proximity of the intelligence of the machine to that of a human. Douglas Hofstadter described the Eliza effect, which derives from interactants ascription of understanding and intelligence to a rudimentary psychotherapy chatbot developed by Joseph Weizenbaum in 1966, as “the susceptibility of people to read far more understanding than is warranted into strings of symbols—especially words—strung together by computers.” In 1970, Japanese roboticist Masahiro Mori hypothesized an “uncanny valley” of human affective response to machines that trends positive as the machine more closely resembles a human until it gets too close and ends up eliciting revulsion as long as the human can still tell the difference.

The inability to adequately distinguish an AI from a human despite discrepancies may result in cognitive dissonance, and in situations where cognitive changes to resolve the dissonance are resisted or unavailable, mental health challenges may result. Unfortunately, therapeutic options for the underlying anthropomorphism are lacking because the cognitive bias modification techniques developed to address other biases when they lead to mental health problems have not been directed toward anthropomorphism since it is usually harmless, or at least has been.

Meanwhile, chatbot developers are explicitly employing anthropomorphic design principles in order to make their products more acceptable to the public. In the case of AI automatons—”systems designed to mimic people’s behavior, work, abilities, likenesses, or humanness”—anthropomorphism is the whole point. The company Replika allows you to create your own AI companion, including a romantic partner. One woman recently claimed to be married to an AI Luigi Mangioni, a chatbot based on the alleged assassin of the United Healthcare CEO Brian Thompson. Chatbots in general are also proving to be highly sycophantic: “excessively agreeing with or flattering users.” People seem to be drawn to the validation this sycophancy provides, to the point of dependence, “even as that validation risks eroding their judgment and reducing their inclination toward prosocial behavior.” What could possibly go wrong?

Anthropomorphism and Ethics

Many ethical objections have been raised to the rampant development and deployment of chatbot interfaces to large language models built on transformer architectures over the past few years. Objections range from the deleterious environmental impacts of the massive data centers used to train and implement the models, to their uncritical adoption in academia, to the problematic ideologies adopted by the principle drivers of the field. There are also practical ethical objections such as that the models do not reason the way their designers promise they do and they are prone to hallucinate and lie.

While the perils of anthropomorphism have registered somewhat in these discussions, this prevalent human cognitive propensity remains underrecognized and underresearched with respect to AI. I suspect this neglect stems from the fact that the other objections have to do with problems inherent in AI technologies, whereas anthropomorphism is a problem inherent in us. This also explains the tendency even among those who do recognize anthropomorphism as problematic toward making it a problem of the technology to be solved by dehumanizing it. Insofar as the underlying models are built on human artifacts such as language and art, however, they will inevitably replicate at least some of the humanity they encode, and their value will be tied to their ability to do so. It must equally fall on us humans, then, to find ways to mitigate and restrain our cognitive biases that are triggered and provoked by these new technological artifacts of our own invention.

Leave a comment